The Secret Language of Pavé: an underrated tool of a jeweler designer

Tiny stones, infinite decisions — a quiet architecture of brilliance.

From a jewellery designer perspective, pavé exists for one simple reason: to control light. When a single stone isn’t enough — when a surface needs presence, rhythm, and continuity — pavé becomes the answer. It allows us to turn metal into a luminous field, using many small stones to amplify brilliance without increasing bulk or weight. Practically speaking, pavé was born from necessity as much as beauty. Early jewelers understood that setting multiple small diamonds close together could create the visual impact of a much larger stone, while remaining flexible, wearable, and structurally sound.

The effect on a jewel is immediate and unmistakable. Pavé changes scale. It softens edges, adds volume without heaviness, and creates movement where metal alone would feel static. A ring band becomes more than a support — it becomes part of the composition. Earrings gain surface and depth without becoming cumbersome. Pendants catch light from every angle, even in low illumination, because pavé doesn’t rely on a single reflection point.

I do. I love pavé!

Historically, pavé has its roots in European goldsmithing, with early forms appearing in 18th-century French jewelry workshops. The term itself comes from pavé, meaning “paved,” like stones laid closely together on a street. That image is not accidental. Just like paving stones, each gem is positioned to support the next, creating a continuous surface designed to be walked across by light. Over time, this foundational idea evolved into multiple techniques — French pavé, griffe pavé, micro pavé, and later invisible settings — each responding to different design needs, tools, and aesthetic sensibilities.

For me, pavé is never decorative by default. It’s a structural choice. It’s how a designer decides whether a piece should whisper or assert itself — whether light should glide smoothly across a surface or fracture into sharper flashes. Understanding why pavé exists is the first step toward using it with intention, not excess.

The quiet precision of micro pavé

Micro pavé is the closest we get to painting with diamonds.

I think of it as pointillism translated into gold — tiny stones (sometimes as small as 0.8 mm) placed so tightly that the metal becomes almost invisible. The beauty comes from restraint: the beads that hold each diamond must be delicate, nearly imperceptible, yet strong enough to endure years of wear.

When executed well, micro pavé creates a soft, almost liquid shimmer. Light moves across it like a sigh. On rings, this technique is ideal for thin, refined bands where you want the stones to feel like part of your skin. In earrings, especially huggies or contoured pieces, micro pavé allows curves to feel uninterrupted — a ribbon of light following the shape of the ear.

But micro pavé is unforgiving. One bead too large, one stone out of alignment, and the entire surface looks noisy. That’s why I choose it when I want intimacy — a design that feels whispered rather than announced.

French pavé — the art of the open V

French pavé is bold in a way micro pavé will never be.

Instead of tiny beads, the setter carves deep V-shaped cutouts between the stones. This exposes the girdle, lets air move through, and releases light from the sides. The result is a sharper, more architectural brilliance — diamonds that feel almost suspended.

When I design a French pavé band, I always think of lace. But not soft lace — the structured kind you find in antique couture corsetry, full of geometry and confidence. French pavé creates more contrast, more sparkle, more drama.

On rings, it gives a sense of openness and volume. On earrings and pendants, it’s extraordinary when you want angular light — pieces where the shimmer is directional, almost staccato. I use it sparingly, because French pavé has a strong personality. It doesn’t whisper; it speaks clearly, unapologetically.

Griffe pavé — claws that draw the eye

The name tells you everything: griffe means claw.

Instead of soft beads or open V’s, the stones are gripped by tiny prongs that rise from the metal. It’s more sculptural than the other pavé styles — every claw adds a small line, a point, a rhythm.

Griffe pavé is wonderful when you want texture. Not roughness, but dimension.

The claws create shadows. The diamonds feel slightly lifted. You see each stone as an individual, yet the surface still reads as a whole.

I reach for griffe pavé in designs that want a bit of tension — a feeling of strength. It works beautifully on bold rings, men’s jewelry, or modern cuffs. On earrings, the claws catch the light in unexpected places, giving depth where micro pavé would give smoothness.

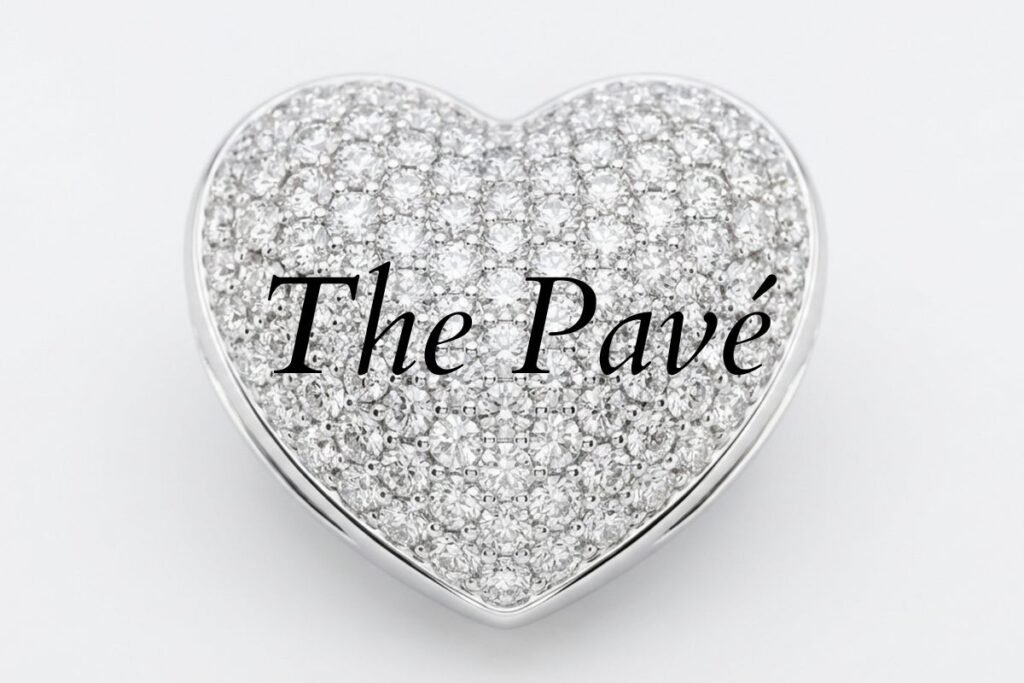

Pavé for bombé shapes — when the surface curves like a breath

A bombé jewel — that soft, domed volume beloved in mid-century design — demands a pavé technique that respects the curve.

You can’t simply follow a straight grid. The stones must radiate outwards, adjusting size and spacing as they climb the dome, much like laying tiles on a rounded vault.

The technical skill here is extraordinary.

Setters often blend sizes, from slightly larger diamonds at the apex to smaller ones along the edges, to keep the continuity perfect. If the alignment falters by even a hair, the curve looks broken.

Bombé pavé has a hypnotic quality — a kind of slow, even pulse. On a ring, it creates a luminous hemisphere that feels generous, decadent. On earrings, especially studs or retro-inspired button shapes, it gives the impression of a full orb of light resting against the skin. It’s pavé in its most sculptural form.

Invisible setting — the illusion of pure stone

Invisible setting almost feels like magic.

The diamonds (usually square cuts like princess or baguette) have delicate grooves cut along their sides. They slide into a hidden metal lattice underneath, locking together with no visible prongs at all.

The result is startling: a surface of uninterrupted gemstones, as if the piece were carved from a single block of light.

But it’s fragile magic. If one stone chips, the entire grid can loosen. This is why I rarely use invisible settings in high-wear rings — they need protection. But in earrings and pendants, where the movement is gentle and controlled, they create a luminous, liquid surface that feels futuristic and almost impossible.

Invisible setting is also emotional for me. There’s something about seeing nothing but stone — no metal, no boundary — that feels like stepping into pure intention.

How pavé changes depending on the jewel

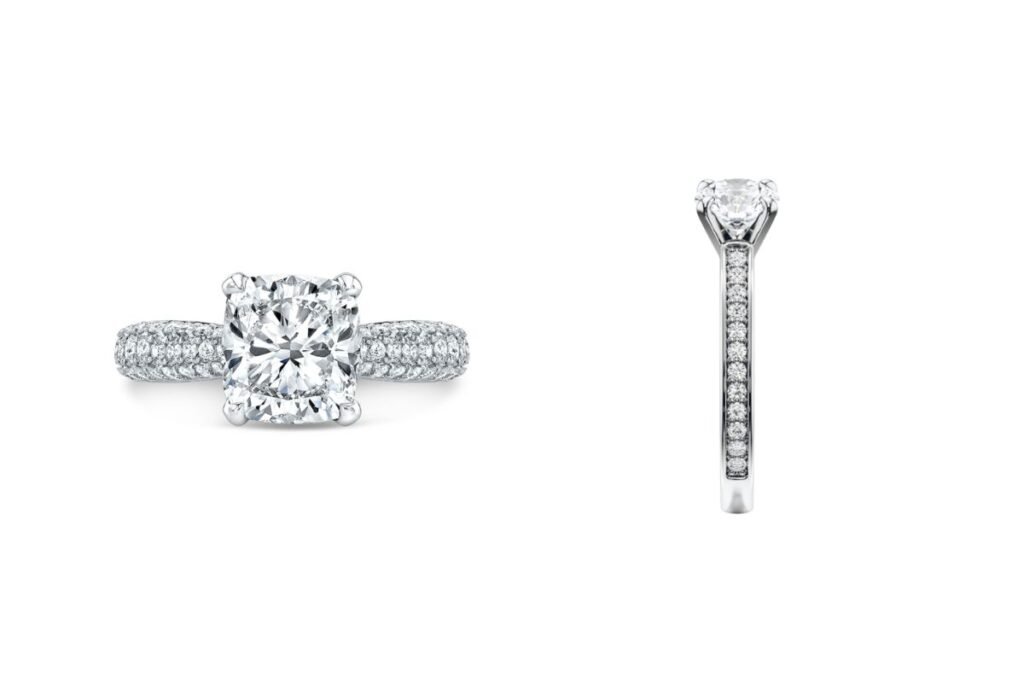

Rings carry the most friction and impact, so the pavé must be both secure and comfortable.

Micro pavé brings elegance to thin bands.

French pavé gives drama to larger silhouettes.

Griffe pavé adds character to bold settings.

Bombé pavé turns a simple ring into a sculptural object.

Earrings ask for coherence. The eye travels along curves; surfaces must feel continuous. Micro pavé and bombé pavé excel here. French pavé works when you want crisp geometry. Invisible setting becomes a centerpiece — a plane of uninterrupted radiance.

Pendants are more forgiving. Their pavé can be delicate, intricate, or experimental, because they lie gently on the body. All techniques are possible — the choice depends on the story the piece wants to tell.

How to choose? What feels right to me…

Among all pavé techniques, the most desirable is often the one that disappears the most — yet remains structurally honest. From a security standpoint, well-executed micro pavé and classic French pavé offer the best balance between brilliance and durability, especially on rings that are worn daily. They anchor each stone independently, allowing the surface to absorb small impacts without compromising the entire setting. Invisible settings, while visually powerful, demand restraint and context; they belong to jewels that are protected by design, not exposed to constant friction.

On a ring, pavé is never neutral. It reshapes proportions, changes how the finger reads, and determines whether the jewel feels architectural or fluid. A thin band with micro pavé elongates the hand. A French pavé shank introduces openness and tension. A bombé pavé transforms the ring into a volume — a presence — rather than a line. These are not aesthetic afterthoughts; they are design decisions that affect comfort, longevity, and how the jewel lives on the body.

Choosing the right pavé means thinking beyond brilliance. How often will the piece be worn? Where will it make contact? Does the design ask for softness or definition, continuity or contrast? Each technique carries its own rhythm and responsibility. The wrong choice can overexpose stones or flatten a form. The right one amplifies intention.

Every pavé decision is ultimately an emotional one. Yes, it’s technical work — measured in millimeters and magnification — but the real purpose is to decide how light should behave once it touches the body. Should it glide? Should it pulse? Should it break into crisp flashes or move as a quiet surface? These choices shape the soul of the jewel long before the wearer ever sees it. And that is what I love most — the quiet truth that pavé, at its heart, is simply the art of teaching light how to gather.