The Flame Between Dawn and Dusk: the Padparadscha Sapphire.

A study in rarity, balance, and the science of a color that almost shouldn’t exist. In my opinion the most romantic gemstone on the planet.

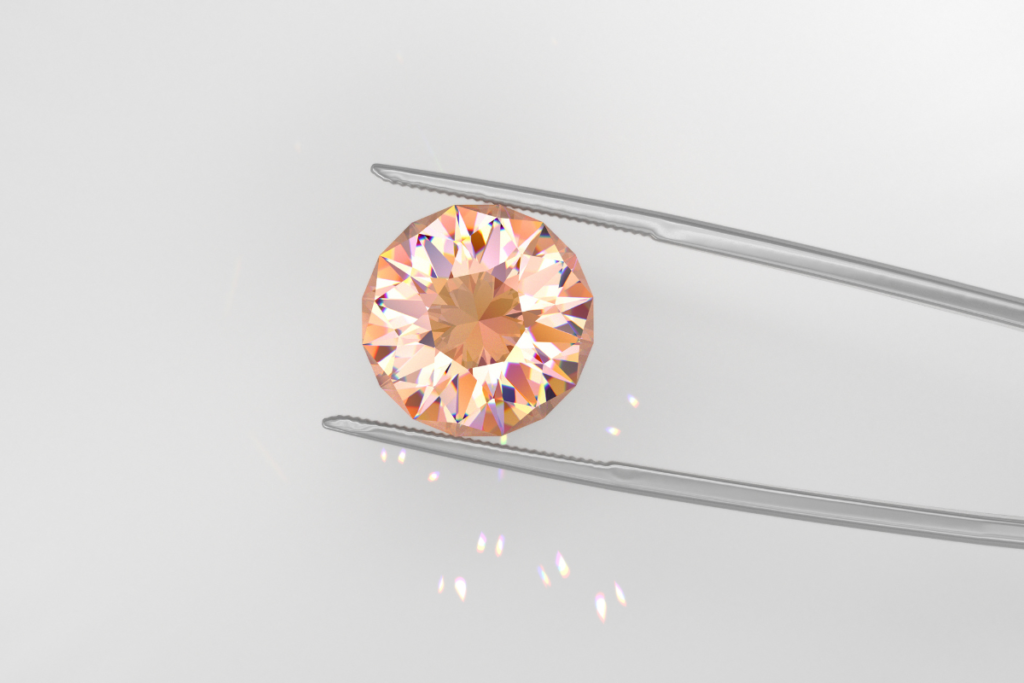

There are gemstones that ask for admiration, and gemstones that command it. Padparadscha belongs to the second group. The first time I held one—small, oval, unassuming in size—I felt the same quiet shock I experience when nature reveals something that seems improbable. A color suspended between two worlds: neither fully orange nor fully pink, but a measured duet of both, like a flame seen through rose-colored glass.

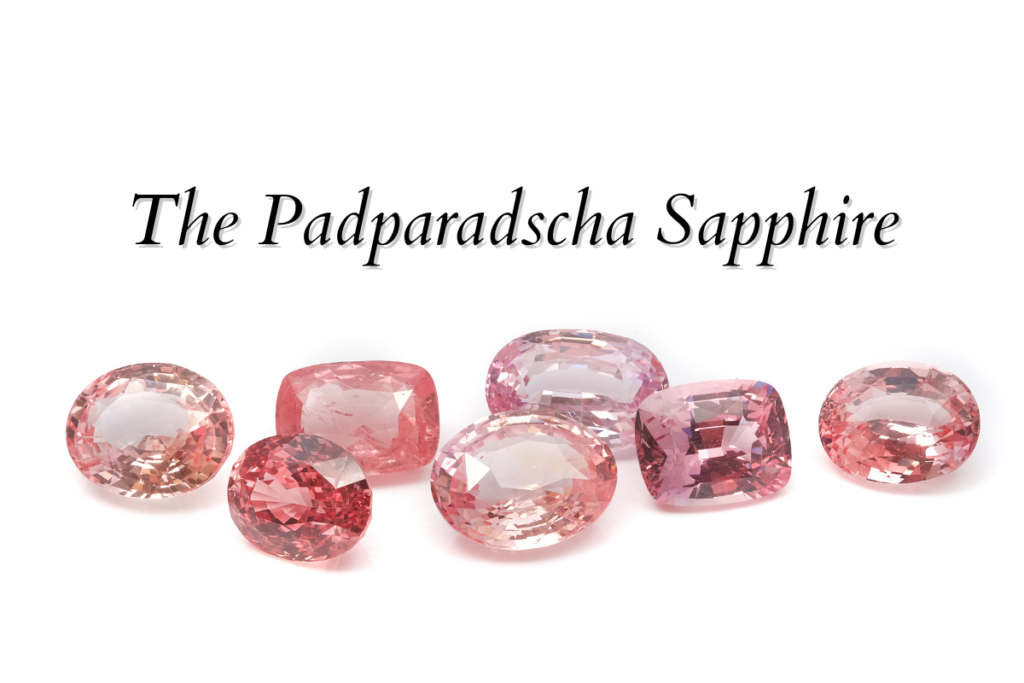

Padparadscha sapphires resist categorization because they sit at the very edge of nature’s palette. Their value, beauty, and near-mythical status come from that fragile balance. A tiny shift in tone, a slightly muddy modifier, or the faintest brown overtone is enough to collapse their identity.

This is not a gem for casual sourcing. It’s a connoisseur’s sapphire—rare, precise, exacting. And it rewards the trained eye.

The birthplace of the lotus glow

Where It Comes From — and Why That Matters

Padparadscha doesn’t come from every sapphire-bearing region.

The color needs a very particular geological recipe: trace elements aligning in proportions so narrow that most deposits never achieve it.

Sri Lanka

This is the heartland. The source people mention first, and the one gemologists recognize as the classical palette. Mining areas like Ratnapura, Balangoda, and Elahera produce the tones closest to the lotus bloom that gave the gem its name. These stones feel airy — almost translucent — with a brightness that reads as sunrise rather than flame.

Sri Lanka’s deposits are mostly alluvial, which means the gemstones have moved tens of thousands of years through rivers and soil before reaching human hands. The journey softens and rounds them. You can often feel this softness in the personality of the color as well. It lifts, instead of sinking.

Madagascar

In the late 1990s, stones from Ilakaka and Sakaraha began surprising the trade. Every so often, a piece appeared with the right balance of pink and orange, deeper in saturation but still honest. Madagascar stones sometimes have stronger personality — slightly more presence, slightly more structure in the color. A fine Madagascan padparadscha can be extraordinary, though the consistency of the Sri Lankan palette still leads the market.

Tanzania

The Umba Valley is known for wild colors — oranges, browns, rusty tones, earth-heavy pinks. Every now and then, one walks close to padparadscha territory, but many carry a weighted personality that bends toward brown or copper. Labs classify very few Umba stones as padparadscha because the color rarely stays clean from all angles.

Other deposits

Small amounts surface in Vietnam and even parts of East Africa, but these stones seldom meet the color criteria. The chemistry simply doesn’t support it. The world doesn’t produce this color easily.

When collectors ask me which origin to pursue, I give a simple answer:

Look at the stone first. There are incredibly beautiful stones from all these regions. But know that Sri Lanka has the deepest historical authority, and that matters in the long run.

A color so fragile it needs its own compass

What makes Padparadscha so rare is not scarcity of sapphire itself—it’s the improbable precision of the color. GIA describes it as a mix of pink and orange, but that simplicity is misleading. Every gemologist I know has stood under a lamp, turning a candidate this way and that, trying to decide:

Is it too orange?

Too pink?

Too peach?

Too brown?

Padparadscha tests your discipline as much as your taste.

The ideal tone is light to medium. Too dark, and the gem loses the lotus translucence that defines it. Too pastel, and it becomes a faint pink sapphire with an orange whisper—charming, but not padparadscha.

Padparadscha is a balance, not a range.

A decision point, not a category.

Heat treatments: acceptable, controversial, and forbidden

Most padparadscha sapphires undergo heat treatment. Traditional heating—used simply to open the color and improve clarity—is widely accepted in the trade. It does not diminish value significantly as long as the resulting color remains natural to the stone’s chemistry.

However, Be-diffusion is another matter entirely. Beryllium can artificially induce the pink-orange blend, and although reputable labs can detect diffusion, stones altered in this way lose all collector legitimacy. They may look bright and enticing, but they are manufacturings of color, not natural phenomena.

When buying, I insist on a major-lab report: GIA, SSEF, Gübelin, or AGL.

Of course, untreated gemstones are a extremely rare and something to look for, as a collector.

However, Padparadscha is too often misrepresented to take chances. So it is very important to have transparency about treatments.

Rarity that borders on the improbable

Why Collectors Value Padparadscha So Highly

Collectors don’t chase padparadscha because it’s “pretty.” They chase it because it’s unlikely.

Three things drive its prestige.

1. The color is geological luck

You can’t manufacture the perfect balance through normal heat. You can’t ask nature to repeat the recipe. The pink and orange only align when trace elements fall into a very narrow window — a window that closes more often than it opens.

For every thousand sapphires sorted in a mine, you might get one stone that even enters the conversation. Then laboratories remove most of those from the category. Padparadscha exists because nature made a rare decision.

2. The category is tightly protected

Labs like GIA and SSEF have clear borders for what counts as padparadscha. If the color leans too far into peach, they refuse the classification. If the tone is too dark, they refuse it. If there’s brown hiding in the shadows, they refuse it. Strict boundaries protect the integrity of the name.

This keeps supply small.

3. Larger stones are genuinely scarce

Most rough that looks promising turns out to be zoned — pink here, orange there — or shows undertones that disqualify it. Even when the rough contains the right color, cutting it without breaking the harmony is another challenge. By the time a clean, balanced stone above two or three carats emerges, years of hands have touched it.

When a collector finally owns a fine padparadscha, they know they’re holding something only a handful of people will ever have in their lifetime. That quiet recognition carries weight.

Sourcing 101: the eye, the light, and the discipline

When I evaluate padparadschas, I begin with one simple test: how the stone behaves in mixed light. Sunlight, diffused studio light, and warm artificial light should reveal the same identity. If the color collapses—if it becomes overly peach indoors or overly orange outdoors—it lacks the stability the gem is known for.

Here’s how I approach sourcing, step by step:

Natural daylight first.

The gem must retain its pink-orange equilibrium without leaning too strongly in either direction.

Warm light second.

This is where stones with hidden brown show their truth.

Face-up impression.

Padparadscha is a light-tone gemstone. If the center of the stone appears murky or shadowed, the cut is fighting the color.

Side-view test.

I inspect for bands of zoning—orange at the ends, pink in the center. Strong zoning interrupts the very essence of the padparadscha glow.

Inclusion pattern.

Silk is common and, in moderate amounts, can actually distribute light beautifully. Large crystals or dark inclusions, however, interrupt the airy nature of the gem and should be avoided at all costs.

This is a stone that rewards patience.

And patience is the only real tool in the sourcing of padparadscha.

What to look for when buying one

Padparadscha’s value is determined by a hierarchy that begins—and often ends—with color. But connoisseurship asks for more.

1. Color: the central decision

A balanced pink-orange tone, free of brown or grey.

Light to medium tone. I like intense but it must be carefully sourced.

Open, luminous, and stable across lighting environments.

2. Clarity: clean enough to protect the light

I tolerate fine silk; it softens the glow. iT;s a romantic and lovable characteristic, in my opinion if not too central or too much a protagonist in the stone.

But dark inclusions, feathers near the surface, and black crystals reduce transparency dramatically. I always avoid that.

3. Cut: precision without heaviness

I prefer ovals and cushions because they respect the stone’s natural habit and maximize light return.

Rounds are rare and often expensive.

Emerald cuts can look austere and emotionless, unless the color is strong.

What matters most is that the cut doesn’t darken the interior. Padparadscha needs an open window, not a closed door.

4. Certification

Always, always from a major laboratory.

GIA, SSEF, AGL, Gübelin, IGI.

If the stone is claimed to be unheated, this must be verified.

Value Outlook for the Next Five Years

I’m careful when speaking about value appreciation, because gemstones aren’t stocks. They follow geology and taste — not quarterly cycles. But padparadscha behaves differently from most colored stones.

Here’s what I’ve seen unfold, and why the next five years look strong:

Supply is tightening

Sri Lanka’s mining regulations are stricter. Many areas that once produced consistent material now yield less, or the stones are smaller. Madagascar’s production fluctuates and doesn’t always offer the clean, light tones collectors expect. Tanzania rarely hits the target.

Limited supply often holds or pushes value upward.

Collectors are shifting toward natural rarities

There’s a growing movement among collectors who want stones defined by geology, not fashion. Paraíba, Jedi spinel, fine alexandrite, and padparadscha sit at the top of that list. These stones have clearly defined identities and tight laboratory standards. Padparadscha benefits from this global shift.

Top-color stones develop long-term loyalty

Collectors don’t sell them easily. They pass them down, or keep them for decades. This keeps the available market supply even smaller.

Laboratory discipline strengthens trust

Because the padparadscha category is so clearly policed, confidence grows. A stable category tends to hold stable value.

Put simply:

A fine padparadscha today will likely be harder to source in five years. The stone you can buy now may not exist in the market later, not because prices change wildly but because supply will continue tightening.

The long-term trajectory favors the patient buyer who chooses color purity over size.

Why collectors pursue it

A well-chosen padparadscha sapphire is not simply rare—it is stable in value because demand follows scarcity, and scarcity is geological, not cyclical.

Collectors are drawn to it for three reasons:

- It is globally recognized as one of the rarest sapphire colors.

No trend can alter that. - Laboratory standards are strict.

This limits the supply of stones that qualify as true padparadscha. - Large, clean, balanced specimens are genuinely scarce.

Even seasoned gem buyers may see fewer than a dozen in their career that truly meet the mark.

My final advice—as a designer and collector

Padparadscha is a study in restraint. The stone teaches you to appreciate balance over intensity. When sourcing, avoid the temptation of bright, neon-like stones that look too orange or too pink. The market is full of “near-pad” gems that seduce the inexperienced eye.

A true padparadscha is quieter, more disciplined.

Its color feels as if it has settled into itself—not fighting, not shouting, just glowing with a calm interior flame.

If you choose one, choose it because its color remains steady across the day.

Choose it because its light is clean.

Choose it because its identity holds under scrutiny.

And most of all, choose it with the knowledge that you are holding one of nature’s rarest equilibria—a moment where geology, chemistry, and time agreed for just long enough to create a lotus-colored ember.

In the end, padparadscha doesn’t try to dazzle.

It breathes.

And in that subtle breath lies its power.