Emeralds: The Stone That Held Kingdoms Together

A meditation on origin, power, and the quiet intelligence of green fire

There are gemstones that feel like beautiful objects, and then there are gemstones that feel like chapters of human history pressed into crystal. Emeralds belong to the second world. Whenever I hold one—especially an old stone with softened edges and a hue that leans toward the blue of deep forests—I feel as though I’m touching the residue of countless hands, rituals, politics, and dreams. Emerald is not simply a mineral born of beryl, chromium, and vanadium. It’s a witness. An archivist. A survivor of empires.

I’ve traced these green lights across continents, from the steep river valleys of Colombia to the high plateaus of East Africa and the ancient tunnels carved into Egypt’s eastern desert. The geography alone could be a book. But emeralds aren’t only about terrain. They are about the way different civilizations understood power—how color became identity, how rarity shaped belief, and how a single gem could influence the destiny of an entire dynasty.

This is the story I return to when I design. Not the mythology of emeralds, though that is rich, but the way real people lived with them: queens, warriors, traders, monks, collectors. Every polished stone I use carries the echo of that lineage, and it’s my responsibility to read it with respect.

I. The Kingdoms That Birthed the Stone

When historians speak of emeralds, they often begin with Cleopatra. Her passion for the gem is part of the legend: she claimed mines, issued her own royal emeralds, and gifted carved stones as symbols of allegiance. But the truth is older. The Egyptians extracted emeralds long before her, from the mines of Wadi Sikait and Wadi Gamal. Those mines still carry the ghosts of workers who carved into basalt with primitive tools under the desert sun. Their stones were pale compared to today’s finest, but they held a magic that captivated the ancient world. To them, green was rebirth—spring, resurrection, and the eternal cycle of life.

Yet the true epicenter of emerald history lies far across the ocean, in what is now Colombia. The deposits of Muzo and Chivor didn’t just produce emeralds. They produced the emeralds that set the global standard for color and saturation—stones so vivid and pure that even modern gemologists still use “Muzo green” as a reference point. According to GIA and decades of Colombian geological study, these deposits were formed under unusual conditions: hydrothermal fluids interacting with black shales rich in organic material. This environment created emeralds of intense color, often with velvety inclusions that make each stone feel like a unique fingerprint.

The Muzo tribe revered these gems as gifts of the earth’s sacred breath. When the Spanish arrived, they were astonished not only by the stones’ beauty but by their abundance. Emeralds became one of the most coveted treasures of the conquest, shipped to Europe in galleons that changed the aesthetic preferences of entire courts. Before Colombian emeralds, European gem culture leaned heavily toward sapphire and ruby. After Colombia, the center of gravity shifted: kings wanted green.

Today, we still classify emeralds through the lens of origin because the land writes its story into the crystal.

- Colombian emeralds: exceptional depth, saturated but never harsh, often slightly bluish.

- Zambian emeralds: cleaner, higher clarity, cooler tones influenced by iron content.

- Brazilian emeralds: lighter greens, sometimes brighter and more open in tone.

- Afghan and Pakistani emeralds: sharp, vivid greens with surprising clarity at smaller sizes.

- Ethiopian emeralds: a newer chapter, with vibrant color but varied stability; still under careful gemological study.

Each region carries a different emotional temperature. A collector who prefers romance and history gravitates toward Colombia. Someone who loves precision and structural beauty might favor Zambia. I’ve learned never to judge quality by country alone. Origin reveals lineage, but the individual stone speaks its own truth.

II. The Science Beneath the Myth

Emeralds are the most human of gemstones because they are imperfect by nature. Inclusions—what gemology calls jardins, or gardens—are not flaws. They are the result of the extraordinary geological tension required to create the gem in the first place. Beryl grows clean in many environments, but emerald needs chromium or vanadium to become green, and these elements rarely join the crystal structure without disruption. That disruption leaves fingerprints.

When I look into an emerald with a loupe, I see rivers, branches, feathers, and planes. I don’t look for absence; I look for harmony. A well-balanced jardin can feel almost painterly. Colombian stones often show three-phase inclusions—liquid, gas, and crystal—tiny worlds inside the gem documented in GIA studies. Zambian stones, shaped by different geology, often appear cleaner with fewer fluid inclusions.

Because inclusions are normal, treatment is common. The most traditional method uses natural cedarwood oil to reduce the visibility of fractures. This is accepted in the trade when done lightly and transparently. Modern methods involve polymers and resins. Those treatments must be disclosed. Any stone in my atelier comes with independent certification—usually GIA or SSEF—because emerald honesty is part of the craft.

Untreated emeralds with strong color and balanced clarity are extremely rare. That rarity is why the market values them so fiercely. Some of the world’s highest auction prices for colored stones belong to untreated Colombian emeralds, especially those from old mines with documented provenance.

III. The Quiet Art and Controversy of Emerald Treatments

There’s a moment in my sourcing work that always feels a little intimate: the instant I tilt an emerald under the lamp and look for the truth of its treatment. Emeralds, unlike many other gems, rarely emerge from the earth in a condition that needs nothing. Their beauty is born through struggle—pressure, heat, fractures, the intrusion of foreign minerals. What people call “flaws” are actually the geological signatures that prove an emerald is real.

Because the stone is naturally fissured, treatment became not a modern invention but an ancient ritual. The earliest evidence comes from Egypt and Rome, where gem artisans filled surface-reaching fractures with oils, waxes, even colorless unguents made from tree resins. They weren’t trying to deceive; they were trying to protect. Emeralds are softer than sapphires or rubies, and the oiling prevents drying, brittleness, or chipping. It made the stone safer to set.

Today, treatment is more complex—both technically and ethically.

Cedarwood Oil: The Old Language of Emeralds

Cedarwood oil is the most traditional method, recognized and accepted by gemological laboratories worldwide. I’ve watched cutters warm the oil gently before placing a newly polished emerald inside. The oil seeps into surface-reaching fissures, making them less reflective and allowing light to cross the stone more freely. When done lightly, this treatment doesn’t hide the gem’s nature; it simply softens the interruptions in its surface.

The scent alone—woody, resinous—feels ancient. I always imagine Roman jewelers doing the same, holding their stones over small clay lamps.

Cedarwood oil has one important characteristic:

it is reversible.

A stone can be cleaned and re-oiled. Nothing permanent is added to the gem. This is why the trade accepts it as part of emerald culture rather than a mark against quality.

Resins and Polymers: The Modern Divide

The modern jewelry world introduced alternatives: colorless resins and polymers that can fill fractures more thoroughly and last longer. These substances create a smoother optical path for light, resulting in a clearer appearance. But they change the conversation.

Resin treatment is more stable than oil; it does not evaporate. It can also make a heavily included stone appear finer than it truly is. This is why the level of treatment—minor, moderate, significant—must always be disclosed.

In my atelier, I refuse stones with anything beyond minor treatment, and I never use resin-filled emeralds in fine jewelry. Not because resin is “wrong,” but because it interferes with the authenticity I value. The jardin—the internal garden—must still be visible and honest.

Color Enhancement: Crossing a Line

There are treatments I consider unacceptable.

The first is dyeing—introducing green tint into fissures to exaggerate the color.

The second is coating—adding a surface layer to intensify saturation.

Experienced collectors avoid these. Reputable laboratories like GIA or SSEF will detect and disclose them. For me, they break the trust between stone, maker, and wearer. An emerald’s hue must be born from chromium or vanadium, not paint.

How Laboratories Describe Treatments

This is where language matters. An emerald report from GIA, SSEF, or Gübelin will typically use one of three categories:

- Insignificant or Minor Clarity Enhancement

Natural. Traditional. Expected.

This is where most high-quality emeralds, even expensive ones, live. - Moderate Enhancement

The stone has more significant fissures. It may still be lovely, but its value changes. - Significant Enhancement

The internal structure required heavy filling. Such stones have a different market.

Collectors sometimes panic when they read “enhanced,” but emerald clarity enhancement is not like treating a sapphire or a ruby with heat. It’s part of the gem’s identity. What matters is degree, honesty, and stability.

How Treatment Influences Value

I’ve seen two emeralds of identical color sell for radically different values because of treatment. The untreated stone—rare, velvety green, filled with natural inclusions that don’t impede beauty—was a treasure. The other, treated with significant polymer filling, demanded a fraction of the price even though its face-up appearance was similar.

Why?

Because collectors prize authenticity.

An untreated emerald is a geological miracle—almost contradictory to the way emeralds form. That rarity fuels auction records and long-term appreciation.

For clients whose priorities are beauty and budget, lightly treated stones are wonderful options. For investors, untreated or minimally treated emeralds are the north star.

The Philosophy Behind Treatment

This is why I love and profoundly hate emeralds. Emeralds are somehow a paradox

They are fragile yet powerful, flawed yet luminous.

Treatment exists because the gem itself demands care.

When you oil an emerald, you’re not altering its soul; you’re easing its breath.

When you fill it with resin, you’re changing the story.

My responsibility is to choose the story that honors the stone. As a designer to ensure quality in setting. Because emeralds easy crack during the setting process.

IV. How I Judge an Emerald

Collectors often ask me what matters most. Color? Clarity? Cut? Origin? There’s no formula, but there are truths shaped by working with hundreds of stones.

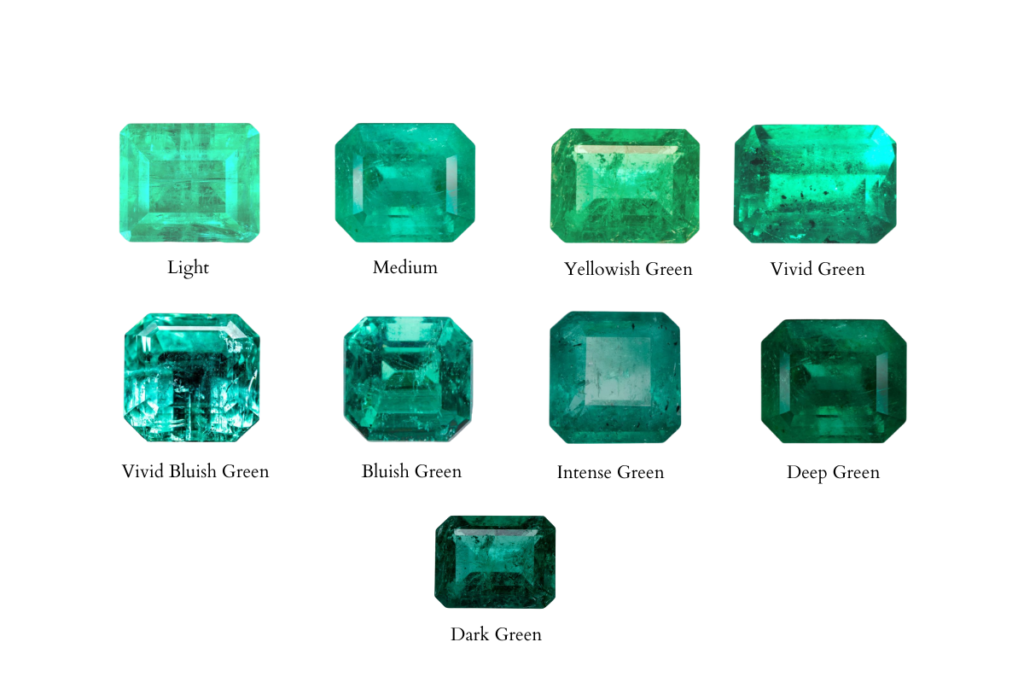

Color is the soul.

The green must feel alive—saturated, deep, neither too yellow nor too blue. Colombian stones often achieve this effortlessly. Zambian material can too, but it expresses itself with a cooler voice.

Clarity is the conversation.

An emerald that is too clean can feel sterile. One that is too included loses strength. I look for a balance that lets light move through the stone without erasing its character.

Cut is the discipline.

Emerald cutting is a negotiation between yield and beauty. A skilled cutter honors the crystal’s internal landscape, opening windows that let color breathe. A poor cut suffocates even the finest material.

Origin is the story.

It doesn’t determine beauty, but it influences value, cultural weight, and the way collectors respond emotionally to a stone.

I don’t care for size as much as proportion. A small but impeccably colored emerald carries more poetry than a large but washed-out one. When I source for clients, I always search for that living pulse—a light inside the gem that doesn’t dim when the stone is tilted in the hand.

V. Rarity, Value, and the Question of Investment

Emeralds have always held value because they are geologically scarce. But their real strength lies in cultural longevity. Civilizations across the world have cherished them—Egypt, Rome, Persia, the Mughal Empire, the Inca and Muisca cultures. That continuity matters. It anchors the stone in collective memory.

Prices vary widely by origin, treatment, color, and clarity. Based on current data from reputable market sources such as IGS, GemSelect, and auction trends:

- Commercial qualities may start in the lower hundreds per carat.

- Fine Colombian or Zambian stones can reach several thousand per carat.

- Exceptional, untreated emeralds—deep color, harmonious clarity, strong provenance—enter the realm of five figures per carat.

- Museum-level stones exceed that easily.

As an investment, emeralds behave differently from diamonds. They’re less standardized, more dependent on individual character. The upside is that exceptional stones can appreciate significantly, especially untreated Colombian gems above 2–3 carats with strong saturation. Provenance—from historic collections or known mines—adds another layer of value.

But I always tell clients one thing:

Buy the emerald whose presence moves you. Financial value follows emotional intelligence.

VI. Sourcing with Integrity

Fieldwork has taught me that ethical sourcing isn’t a marketing phrase. It’s a lived practice. Emerald mining can be difficult, even dangerous work, especially in regions with complex political histories. I source primarily through partners in Colombia, Zambia, and Brazil who maintain transparent chains of custody and work closely with local communities.

When I evaluate a stone’s path—mine, cutter, dealer—I look for honesty at every step. A gem should carry no shadow of ambiguity. The energy of a piece of jewelry begins long before it reaches the bench. Clients may not see this process, but they feel it in the final piece.

VII. The Long Memory of Emeralds

If you trace human history through emeralds, a pattern emerges. These stones appear at the crossroads of power and devotion.

Cleopatra used emeralds to assert sovereignty.

The Mughal emperors carved verses of protection into them.

Spanish galleons turned them into currency of conquest.

European royals wore them as symbols of divine right.

Indigenous Colombian cultures saw them as living pieces of the earth’s blood.

Every time I set an emerald in gold, I feel the weight of those stories. Not as burden, but as inheritance. The gem becomes a bridge—between centuries, between hands, between the private inner world of the wearer and the vast sweep of human history.

There is a reason emeralds endure.

Green is the color of life, but also of judgment. It asks: What do you value? What do you carry forward? What do you protect?

An emerald doesn’t shout. It contemplates. It waits. It speaks when you are ready.

Closing Reflection

Whenever I finish a piece centered on an emerald, I hold it for a moment before letting it go. I watch how the green shifts as I turn it in my fingers—soft at first, then deeper, then suddenly luminous when a beam of light hits the right angle. That movement feels like breathing.

To me, an emerald is never just decoration. It’s a reminder that beauty can hold memory, that history can live in color, and that the earth still writes poetry in mineral form. When you wear it, you’re not only carrying a gem. You’re carrying a fragment of the world’s long story, and—quietly—your own.